On Being A Student & Beginning Writing

Editor’s Note: Dear Reader, we’ve unlocked a few posts from the archive that originally went up behind the paywall. If you’re still a free subscriber, we invite you to go back, read up, and consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Cheers!

On Being a Student

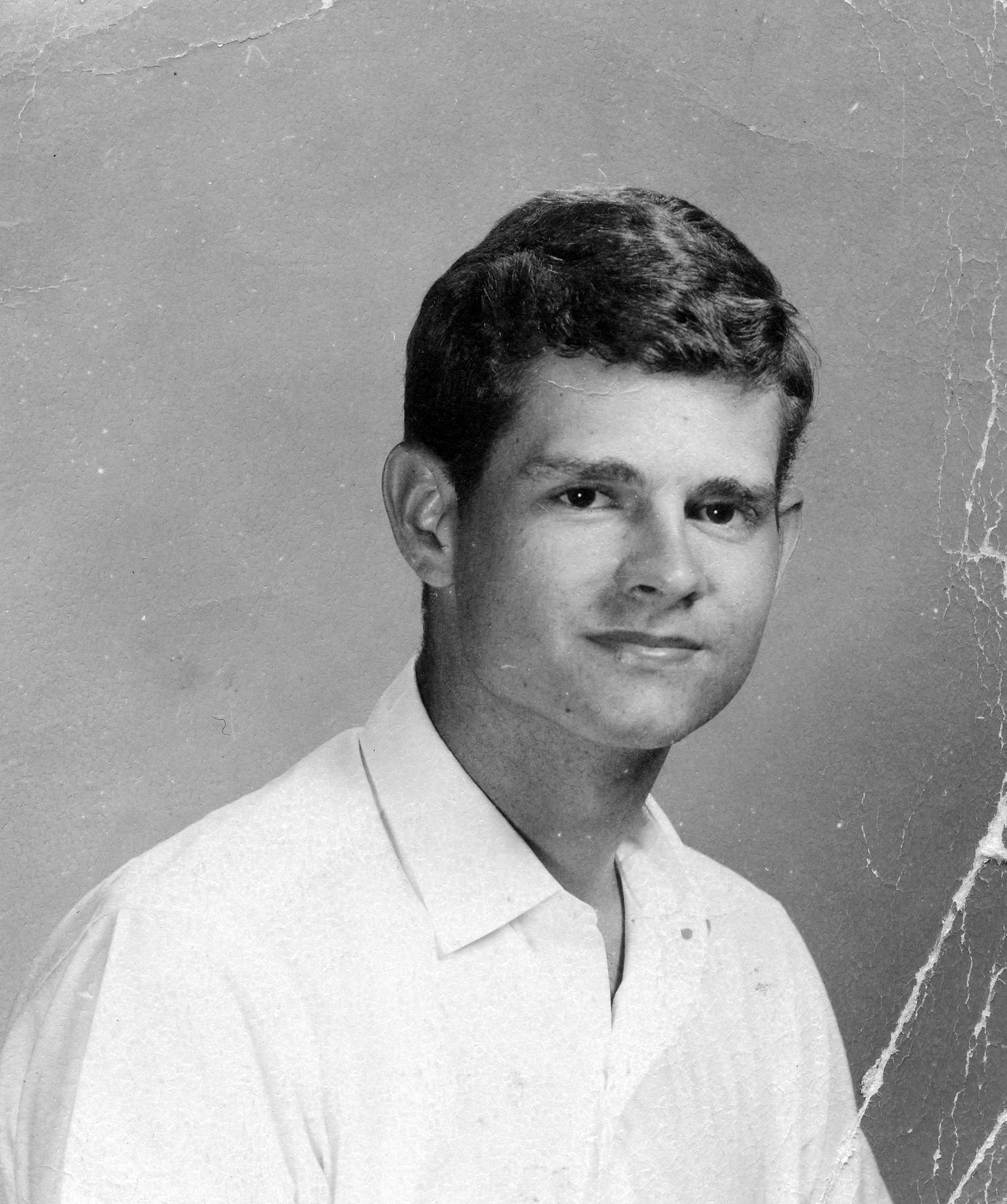

I began my career as a student in the Perryton school system in 1950 and graduated from high school in 1962. I performed well and made good grades until the fifth grade, and at that point I began losing interest in schoolwork.

As a scholar, I probably bottomed out in my sophomore or junior year in high school, when I came close to failing algebra, plane geometry, and chemistry.

There was no mystery about it. I just didn’t care about grades, and, oddly, I don’t recall that my parents did either. I studied the bare minimum and tried to stay off the failing list.

The football coaches kept a close eye on our grades and delivered swats to the athletes whose names appeared on the failing list. In the ninth grade, I collected a number of swats and did it with pride. I even aspired to setting the school record for Most Swats in a Single Week.

That changed when Coach Ogden delivered three bombshells that almost melted my shorts. He found an effective way of saying, “Maybe you shouldn’t flunk algebra.” They say that when you’re trying to teach a donkey, sometimes you have to start with a two-by-four.

The swats I received had nothing to do with cruelty. They were part of a game that I enjoyed until it became too painful.

In my senior year I decided to become a better student and did the first earnest studying of my life—not enough to make me an honor student, but enough to get me accepted into college the following September.

I should have been an avid reader but wasn’t. Both my parents felt a reverence for the written word. They subscribed to a number of magazines (Reader’s Digest, Time, Life, National Geographic, Boy’s Life, The Baptist Standard, Wisdom, and Ladies Home Journal). They belonged to several mail order book clubs, and displayed their large collection of books on floor-to-ceiling shelves in our living room.

They hired a carpenter to build bookshelves in my upstairs bedroom and Mother filled them with books, hoping I would read them.

I was a restless outdoors boy and a slow reader. I am still a slow reader. I wonder if I might have been dyslexic at a time when nobody had ever heard of it. I wonder about that because over the years, I have gotten a great deal of mail and feedback from people who have had some experience with dyslexia.

They all made the same point, that kids with dyslexia have found the Hank books easy and pleasant to read.

Today, I meet students who are reading my books in the first and second grade. I don’t remember reading much of anything until fourth grade, although Mother often read aloud to me when I was young, usually Bible stories or nature articles from Reader’s Digest.

I started many books, sensing that it was something I ought to do, but usually jumped ship after a chapter or two. I did finish several of the Sugar Creek Gang adventures by Paul Hutchens, and enjoyed them, but beyond that and the novels of Mark Twain, I had no interest in fiction.

My reading tended to be driven by impulse and curiosity. On stormy days, I would drift over to the library wall in the living room and choose a magazine with pictures, sit down on the sofa, and turn pages until I found a subject that caught my interest. Life and National Geographic were my favorite magazines.

I also had a warm relationship with our set of World Book encyclopedias. I would choose a volume at random and spend hours turning pages, looking at the illustrations, and reading the sections that interested me.

Even today, my reading tends to follow my curiosity, and the pile of books beside my bed might include Winston Churchill’s History of the English-Speaking People, a biography of C.S. Lewis, the memoir of a New Mexico rancher, books on ancient Egypt, modern science, Iran, mythology, and Texas Panhandle archeology.

The only fiction would be Hank books. I love those books and when I can’t find anything else that stirs my interest, I read Hank…and laugh out loud.

On Beginning Writing

It might sound odd, but those of us who lived in little towns in West Texas during the Fifties didn’t know that becoming an author was something we could aspire to. I guess we thought that authors lived somewhere else (New York, Boston, or London), and most of them were dead.

The people in my family wrote good letters and spoke grammatical English. In fact, they were rather militant about it. Speaking careless English in our home was not tolerated. But no one in my family or town had ever written a story or novel, so we never thought that a career in writing was a possibility.

Through elementary, junior high, and most of high school, I never wrote a story or a poem, either in school or on my own. I did, however, receive serious drilling in grammar and sentence structure, and in the eighth grade, I was introduced to sentence diagraming.

Mrs. Dunkle was our teacher, a tiny woman who wore heavy lipstick and whose dark features reminded me of Minnie Mouse. Her voice had a bit of a rasp due to her consumption of cigarettes. In spite of her size, she was not the least bit intimidated by eighth-grade boys who towered over her, played football, and thought we were tough.

In toughness, we were pretenders. She was the real deal. She had a sharp tongue that could slice up a cocksure eighth grade boy in seconds, and she did it without remorse. I know, because I tested her on several occasions. I had a special gift for luring a teacher off the subject, but it never worked on Mrs. Dunkle. She had her lesson plan, she stuck to it, and she didn’t care that we considered her the meanest teacher in the entire school system.

Mrs. Dunkle was a firm believer in the importance of sentence diagramming: subject, verb, object, and modifiers. For nine months, we studied our national language as a contractor would analyze the electrical and plumbing diagrams on a blueprint. I didn’t know it at the time, but it was excellent preparation for my future profession as a writer, and probably better than any kind of creative writing I might have done.

Even today, I diagram sentences in my head, and if I were teaching a course in writing, I would begin with sentence diagramming. Thank you, Mrs. Dunkle.

It was in my senior year that I did my first creative writing and began to suspect that I might have a talent. That knowledge came my way through another English teacher, Annie Love, a dear lady who had taken on the burden of teaching Chaucer and Shakespeare to donkeys like me, and to some who were even worse than me.

Somehow, she loved us and wanted to share her deep affection for English prose and poetry. She read Chaucer aloud with the skill of an actress, actually smacking her lips as the delicious words rolled off her tongue.

When this failed to penetrate our armor-plated skulls, she called on another talent, a voice that could be as shrill as a train horn. Once provoked, she turned it on and let us have it. I’m sure that Mr. Zoller, the principal, heard complaints about Mrs. Love screeching at her kids, but I doubt that he said much about it.

He knew what he had in Annie Love—an extraordinarily gifted teacher who was adored by her students—and he left her alone.

When Mrs. Love gave us the assignment of writing an original poem, I heard loud groans from other members of the football team, Johnny Leicht in particular. Johnny was a farm kid, a close friend, and always an A student. He had no trouble solving algebra equations or calculating the right answers on a chemistry exam, but the prospect of writing a poem plunged him into despair.

With me, it was just the opposite. Chemistry and algebra baffled me, but somehow I knew I could write a poem.

Mrs. Love gushed over it. “Oh, this is so beautiful! Will you write me another one?” For the rest of the semester, I wrote poems for her, and she kept telling me they were beautiful. They weren’t all that good—they were probably pretty bad—but her approval meant a great deal to me.

I wouldn’t have written poems for a grade or even for money, but I stayed up late many nights, listening to Bach and writing poems for Mrs. Love.

At certain points in a young author’s life, it is very important that someone says, “This is beautiful!” She was a dear, dear lady, and years later, I dedicated one of the Hank books to her.

Thank you, John, for sharing stories about your education. I feel a strong kinship with them. There had never been a writer in my family, at least not one that I knew about, and it never occurred to me that I might become a writer, although I always loved my English teachers and signed up for the ones with the reputation of being hard teachers.

One of the most important decisions I ever made was to sign up for a full year of typing. (“Why on earth do you want to take typing?” was my mom’s wondering comment.) I had had a 9-week introductory course in 8th grade Exploratory, and I was good at it, liked it, but didn’t know why.

I always made good grades, because my mother insisted, even to the point of refusing to sign my report card when I made a C in math. I graduated from Stephen F. Austin High School in 1955, but it wasn’t until the the early 80’s that my daughter published four volumes of letters that I had written to her while she was in college that I actually realized that I was a writer.

In 1993 my husband was offered a “part time” job teaching geography and education at ACU, and I had the opportunity to work toward a master’s in creative writing, which I completed not long after my 60th birthday. I am just now getting a manuscript ready for publication, a collection of devotionals published online anonymously in 2000, inspired by Words written 2,000 years previously.

Thank you for your autobiography. My husband and I have both read it and found it encouraging and inspiring. Hooray for hawking your books from the back end of your pickup at rodeos! Our grandsons loved your Hank books! Bless you!

Your grateful reader,

Dale Ogren and husband Al

Buhl, Minnesota